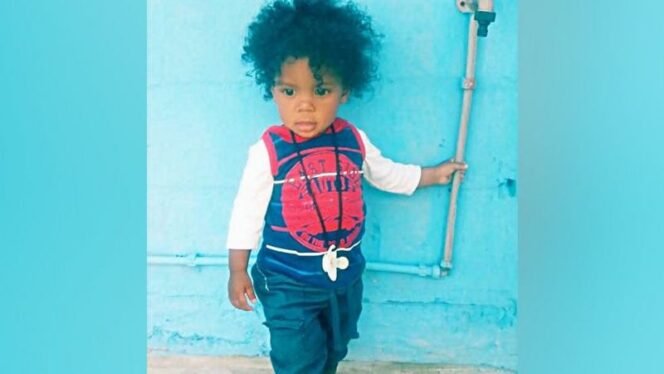

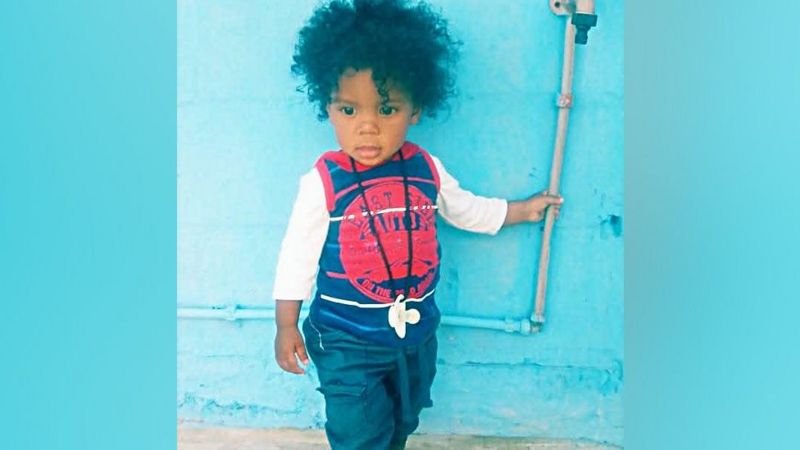

In the Cape Flats—a sprawling area of underdeveloped townships outside Cape Town—life is a daily battle for survival. Plagued by drug trade, poverty, and entrenched gang violence, communities here are still reeling from the legacy of apartheid. The human cost is devastating. For Devon Africa and his wife, Undean Koopman, the tragedy is deeply personal. Their four-year-old son, Davin, was killed in February, caught in the crossfire of a gang shootout—just two years after their 12-year-old daughter, Kelly Amber, met the same fate. Their heartbreaking story is not an isolated incident, but a reflection of the widespread suffering caused by gang warfare in South Africa’s Western Cape.

I. The Anatomy of a Crisis

1. Apartheid’s Lingering Shadow

The Cape Flats were born out of apartheid-era forced removals that displaced non-white populations from Cape Town’s wealthier neighborhoods. These relocations created pockets of economic stagnation, where state investment was minimal, and basic infrastructure crumbled. Generations of residents have lived in deprivation—fertile ground for gang culture to take root.

2. The Numbers Paint a Grim Picture

According to the South African Police Service (SAPS), the Western Cape consistently records the highest rate of gang-related murders in the country. Townships like Wesbank and Hanover Park are particularly hard-hit, becoming virtual war zones where stray bullets are common and children grow up in fear.

II. Why Gangs Thrive in Cape Flats

1. Gangs as Community Providers

“Gangs flourish in areas that the state has neglected,” explains Gareth Newham, head of the Justice and Violence Prevention Programme at the Institute for Security Studies. In communities without functioning government services, gangs fill the void. They offer food, pay school fees, cover transport costs, and even fund funerals. This embedded presence makes it difficult for law enforcement to uproot them—gang members use civilians’ homes to store weapons and drugs, blurring the lines between criminal and community.

2. Generational Recruitment

Gang affiliation often begins in childhood. Recruiters target youth as young as eight years old. Children are born into this lifestyle, sometimes with entire families linked to a specific gang. The normalization of violence means that by adolescence, many are already engaged in criminal activity or battling drug addiction.

III. Failed Government Interventions

1. Ramaphosa’s Task Forces and Military Deployment

In 2018, President Cyril Ramaphosa launched a special unit to combat gang violence and briefly deployed the army to the region. However, these efforts had minimal long-term impact. Arresting gang members does little to dismantle the structure—they are simply replaced by younger recruits. Without addressing the root causes—poverty, unemployment, and drug abuse—the cycle of violence continues unabated.

2. Lack of Trust in Law Enforcement

The community’s relationship with police is fraught with mistrust. Many residents fear calling the police, unsure whether they will show up—or worse—whether the officers themselves are involved in corruption. This lack of faith renders official interventions ineffective, forcing communities to seek their own solutions.

IV. Community-Led Solutions: A Glimmer of Hope

1. Pastor Craven Engel’s Peace Mediation

Fifteen kilometers from Wesbank, in Hanover Park, Pastor Craven Engel is fighting a different kind of war—one of peace and reconciliation. He mediates between warring gangs, aiming to halt violence through negotiation and rehabilitation. His formula: detect conflict, interrupt it, and shift mindsets.

“The biggest economy here is the drug trade,” says Pastor Engel. “There’s no formal employment, so people survive through the drug culture.”

His church used to receive government support, but now relies on charitable donations to run rehabilitation programs, provide job training, and help former gang members transition into peaceful lives.

2. The Power of Rehabilitation

Pastor Engel’s program sends reformed gang members back into the community to broker peace. One such individual, Glenn Hans, uses his own experience to convince active gangsters to consider a ceasefire.

Still, not everyone is convinced. During a peace negotiation, one gang member bluntly admits: “The more we kill, the more ground we seize… I can’t ensure peace. That’s not my decision.”

Despite frequent setbacks—like ceasefires broken within days—Pastor Engel persists, believing change is possible, one person at a time.

V. The Battle for Redemption

Fernando “Nando” Johnston, a member of the Mongrels gang, seeks a way out. “In this game, you either go to jail or die,” he says. Raised in a gang-involved family, Nando is determined to change. He joins Pastor Engel’s 6–12-week rehab program to get clean and find employment.

His mother, Angeline April, is cautiously hopeful. “Please just make the best of this opportunity,” she pleads. “I love you very much.”

Two weeks into the program, Nando is drug-free, seeing his family, and participating in a job readiness initiative. For once, there is a sense of progress.

VI. The Relentless Reality for Many

1. When Hope Feels Out of Reach

While some find their path to healing, others remain trapped in the cycle of violence. In Devon and Undean’s home—scarred by bullet holes and silent with grief—hope is elusive. Their loss represents thousands more who have suffered under the weight of unending violence.

2. Communities Abandoned

Mr. Newham emphasizes the dire situation: “Politics has clearly failed these communities.” Residents have given up on help from government or foreign intervention. Local leaders like Pastor Engel carry the burden of change almost entirely on their shoulders. “There’s no magic wand. No one is coming to save us,” he says. “We must build resilience ourselves.”

Conclusion: A Call for Structural Change and Local Empowerment

The tragedy unfolding in Cape Flats is not the result of isolated criminal activity—it is a systemic failure rooted in historical injustice, socioeconomic neglect, and governmental apathy. Gang violence is not just about turf wars and drugs. It’s about families torn apart, children buried too soon, and communities left to fend for themselves.

While community leaders like Pastor Engel provide a crucial lifeline, the solution must go deeper. Structural reforms are needed to address poverty, education, employment, and mental health. Policing alone cannot fix what decades of neglect have broken.

And yet, amid the darkness, there is a glimmer of hope. For every Davin lost, there is a Nando trying to break the cycle. The fight for peace in the Cape Flats may be uphill, but as long as voices rise against the violence—both within and beyond the community—change remains possible.