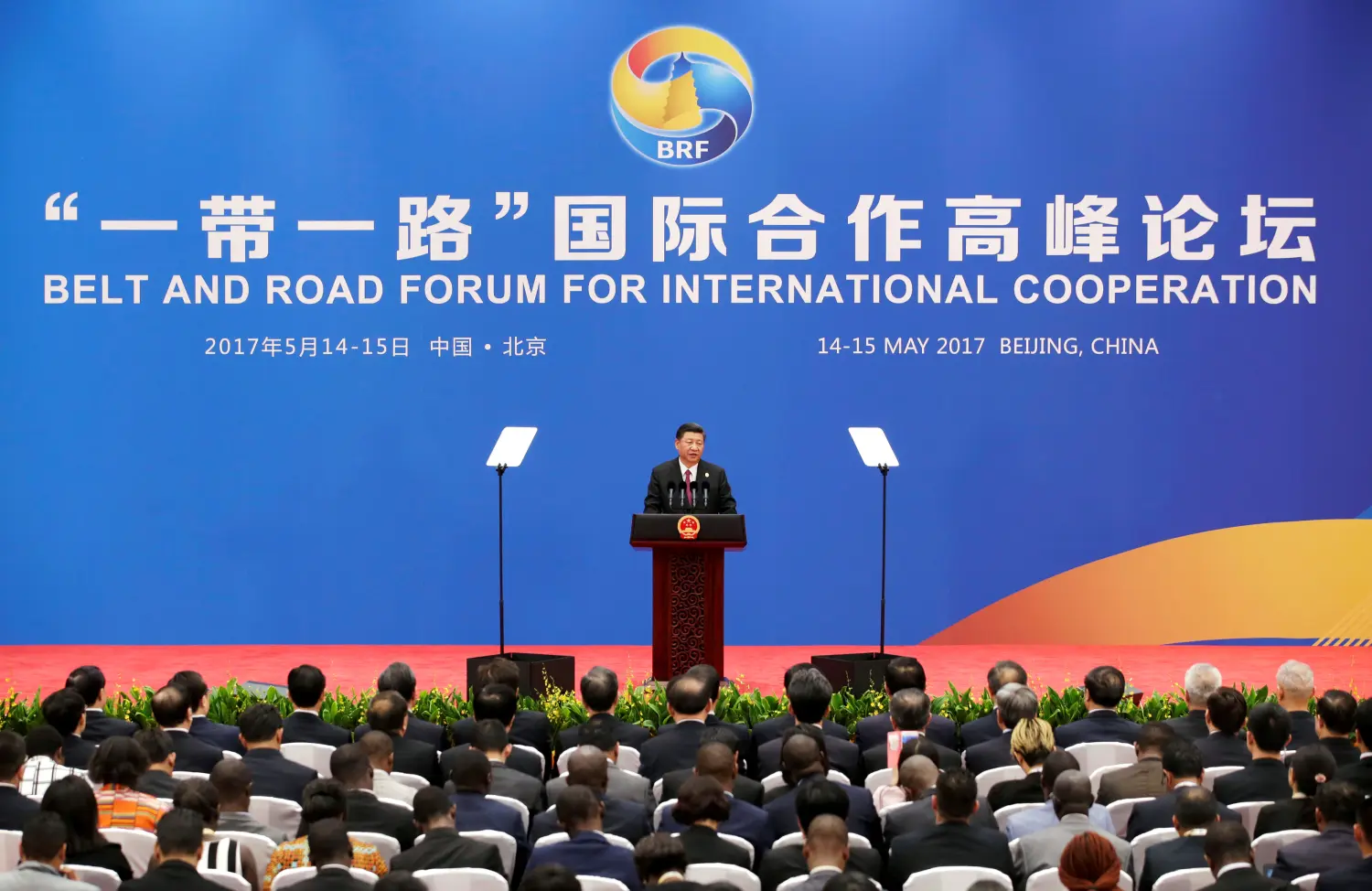

China’s global infrastructure ambitions, most prominently embodied in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), represent one of the most expansive geopolitical and economic strategies of the 21st century. Launched in 2013 by President Xi Jinping, the BRI seeks to connect Asia, Africa, and Europe through a vast network of roads, railways, ports, energy pipelines, and digital corridors. The initiative promises to bolster global trade, foster economic development, and reinforce China’s status as a global power.

However, as the BRI enters its second decade, the bold vision faces mounting challenges. The strategy is increasingly entangled in economic uncertainty, geopolitical friction, and domestic pressures within China. From growing debt risks in partner countries to pushback from Western governments and rising competition in global infrastructure financing, the BRI is confronting headwinds that threaten its sustainability and influence.

This article assesses the major economic and political risks facing Beijing’s global infrastructure strategy today. It examines internal economic constraints, debt and governance issues in partner nations, growing geopolitical tensions, and the evolving international response—all of which are shaping the future trajectory of China’s global infrastructure diplomacy.

1. Internal Economic Pressures on China

a. Slowing Economic Growth

China’s economy, once growing at double digits annually, has begun to decelerate. Structural challenges such as:

-

A shrinking labor force,

-

Slowing productivity growth,

-

A struggling real estate sector,

-

And weakening domestic consumption

are putting pressure on Beijing’s ability to sustain large-scale overseas investments.

While China’s GDP growth rebounded slightly post-COVID, long-term projections suggest a lower growth path. As a result, fiscal space is tightening, making it harder to continue funding overseas projects with the same intensity as in the past decade.

b. Rising Debt and Financial Strains

The Chinese government and its state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are facing rising debt levels, particularly due to domestic stimulus efforts and a need to shore up economic growth. Many BRI projects were financed through Chinese policy banks and SOEs, often with low returns or high risk profiles. Mounting defaults in partner countries have added further strain.

In response, China is reportedly reassessing its BRI financing model, placing more emphasis on:

-

Smaller, high-impact projects,

-

Commercial viability,

-

And risk-sharing with international institutions.

2. Economic Risks in Partner Countries

a. Rising Debt Vulnerabilities

One of the most persistent criticisms of the BRI has been the issue of debt sustainability. Many recipient countries, eager for infrastructure investment, have taken on large debts without clear mechanisms for repayment. According to the World Bank and other observers, over a dozen low- and middle-income countries are now considered at high risk of debt distress due to Chinese loans.

Examples include:

-

Sri Lanka, which handed over the Hambantota port on a 99-year lease to a Chinese company in a widely criticized debt-for-equity swap.

-

Pakistan, whose BRI-linked energy and transport projects under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) have strained national finances.

-

Zambia and Kenya, facing mounting debt from Chinese-financed railway projects.

b. Project Delays and Cost Overruns

Many BRI projects have faced delays, inflated costs, or underutilization. Reasons include:

-

Poor planning,

-

Lack of feasibility studies,

-

Political instability in host countries,

-

Environmental and social backlash.

These problems not only erode economic returns but also undermine local trust in Chinese involvement, contributing to a growing backlash in various regions.

c. Corruption and Governance Challenges

BRI projects have occasionally been linked to corruption scandals, opacity in contracts, and weak compliance with international standards. Such issues:

-

Undermine long-term sustainability,

-

Foster resentment among local populations,

-

Expose Chinese firms to reputational risks.

3. Growing Geopolitical Tensions

a. Strategic Competition with the West

China’s global infrastructure push is increasingly viewed through the lens of strategic rivalry, particularly by the United States and its allies. Initiatives like:

-

The G7’s “Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment” (PGII),

-

The EU’s Global Gateway, and

-

The Blue Dot Network (a U.S.-led initiative for infrastructure transparency)

have emerged as counterweights to the BRI.

Western policymakers argue that the BRI:

-

Advances Chinese political influence,

-

Embeds clientelism in foreign policy,

-

And exports authoritarian models of development.

This framing has led to heightened scrutiny of BRI projects, especially in politically sensitive areas like:

-

Africa’s digital infrastructure,

-

European port acquisitions,

-

And Southeast Asian rail and energy corridors.

b. National Security Concerns

BRI-related investments in critical infrastructure—like ports, telecommunications networks (e.g., Huawei’s 5G), and data centers—are increasingly seen as national security threats. Some host governments have:

-

Canceled projects due to strategic concerns,

-

Implemented tighter foreign investment screening,

-

Or shifted toward alternative development partners.

This has fueled diplomatic tensions and reduced China’s ability to operate in certain strategic sectors.

c. Political Backlash and Resentment

In several partner countries, citizens and opposition parties have voiced concerns over:

-

Lack of transparency,

-

Job displacement (due to Chinese labor imports),

-

Environmental degradation,

-

Loss of sovereignty.

In places like Malaysia, the Maldives, and Tanzania, newly elected governments have renegotiated or canceled Chinese-backed projects. This political volatility increases uncertainty for long-term Chinese investments.

4. Evolving Strategy: From “Hard” to “Smart” BRI

In response to these mounting risks, Beijing has adjusted its BRI strategy in several notable ways:

a. “Small Is Beautiful” Approach

China is increasingly promoting smaller-scale, community-level projects that:

-

Are easier to manage,

-

Have quicker payoffs,

-

Face less geopolitical scrutiny.

These include:

-

Rural solar energy installations,

-

Public health infrastructure,

-

Educational partnerships.

b. Emphasis on Green and Digital BRI

In recent years, Beijing has branded the initiative as the “Green BRI” and “Digital Silk Road”, with an eye toward:

-

Sustainable energy development,

-

Digital infrastructure,

-

Innovation and technology transfers.

However, skepticism remains, particularly regarding the environmental integrity of Chinese-backed projects and the implications of digital surveillance technologies being exported to authoritarian regimes.

c. Increased Multilateral Engagement

China has sought to collaborate more with international institutions like the UNDP, World Bank, and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) to improve transparency, risk assessment, and social safeguards.

This multilateral turn is partly aimed at addressing criticism and reducing the perception of the BRI as purely a geopolitical tool.

5. Future Scenarios and Strategic Implications

Given the current landscape, several scenarios could shape the BRI’s evolution over the next decade:

a. Contraction and Consolidation

China may scale back its overseas infrastructure ambitions and focus on:

-

Existing project completion,

-

Debt restructuring,

-

High-return investments.

This would mark a shift from expansion to consolidation, with reduced risk appetite from Chinese banks and firms.

b. Regionalization of the BRI

Rather than an all-encompassing global project, the BRI could become more regionally focused, particularly in areas where:

-

Political alignment is stronger (e.g., Central Asia),

-

Infrastructure needs are dire,

-

Debt concerns are lower.

Southeast Asia, Central Asia, and parts of Africa may become the core focus zones.

c. Greater Alignment with Global Standards

To remain viable and competitive, Beijing may increasingly align BRI projects with global norms on:

-

Environmental and social impact,

-

Procurement transparency,

-

Debt sustainability.

This shift would help China remain a relevant infrastructure player amid growing international scrutiny.

6. Strategic Implications for the Global Order

a. Multipolar Infrastructure Competition

The BRI has effectively catalyzed a multipolar competition in global development finance. The world is seeing an era of infrastructure diplomacy, where:

-

Developing countries can leverage multiple suitors,

-

Standards are evolving through competition,

-

Geopolitical influence is exercised through concrete and steel.

b. Shifting Soft Power Dynamics

While the BRI enhances China’s influence in the Global South, backlash and economic risks could erode its soft power appeal. Countries may increasingly view Chinese aid with mixed sentiment—valuing the funding but wary of the conditions.

c. Testing China’s Global Governance Model

The BRI is also a test case for China’s ability to shape global rules and norms. Its success or failure will reflect on the viability of alternative models to Western-led development, particularly in authoritarian or hybrid regimes.

Conclusion: A Strategy Under Pressure, Not Defeated

China’s global infrastructure strategy, while ambitious and historically transformative, now faces a critical inflection point. Internal economic pressures, unsustainable debts, political backlash, and growing geopolitical pushback have all complicated Beijing’s ability to execute its BRI vision as originally conceived.

Yet, rather than abandoning the strategy, China appears to be refining and recalibrating it—focusing on smaller, greener, and smarter projects, with greater attention to transparency and multilateralism.

Whether the BRI ultimately thrives or recedes will depend on China’s capacity to manage risk, adapt to new realities, and respond to legitimate concerns—not only from governments but from communities and civil societies across the globe.

The coming years will show whether the Belt and Road becomes a lasting pillar of international cooperation or a cautionary tale of overreach and political backlash. In either case, the BRI has already changed how the world thinks about infrastructure, power, and connectivity in the 21st century.