In the intricate web of global energy politics, one of the most transformative developments of the 21st century is the emergence of new routes and alliances to deliver natural gas from Central Asia to Europe. As the European Union (EU) continues to seek alternatives to Russian energy and diversify its energy supply, Central Asia – a region rich in natural gas reserves – has come into sharper focus. The landmark project to facilitate the transport of gas from Central Asia to Europe represents not just an engineering feat, but a geopolitical realignment with vast implications for energy security, international trade, and regional diplomacy.

1. The Strategic Imperative: Why Central Asia Matters

Central Asia, encompassing countries such as Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, possesses vast hydrocarbon reserves. Turkmenistan alone is estimated to hold the fourth-largest natural gas reserves in the world. Historically, much of the region’s gas exports were routed through Soviet-era infrastructure that fed into Russia, giving Moscow significant leverage over its southern neighbors and downstream consumers in Europe.

However, rising tensions between Russia and the West—particularly following the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the 2022 invasion of Ukraine—have prompted Europe to urgently seek new, secure, and politically independent sources of energy. In this context, connecting Central Asia directly to European markets is both an economic opportunity and a strategic necessity.

2. The Trans-Caspian Pipeline (TCP): A Long-Awaited Dream

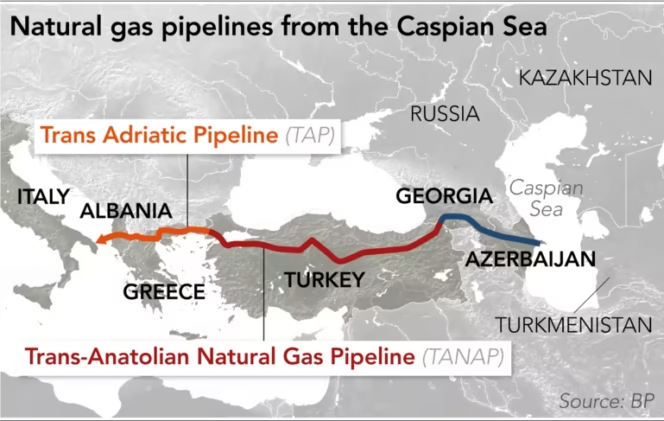

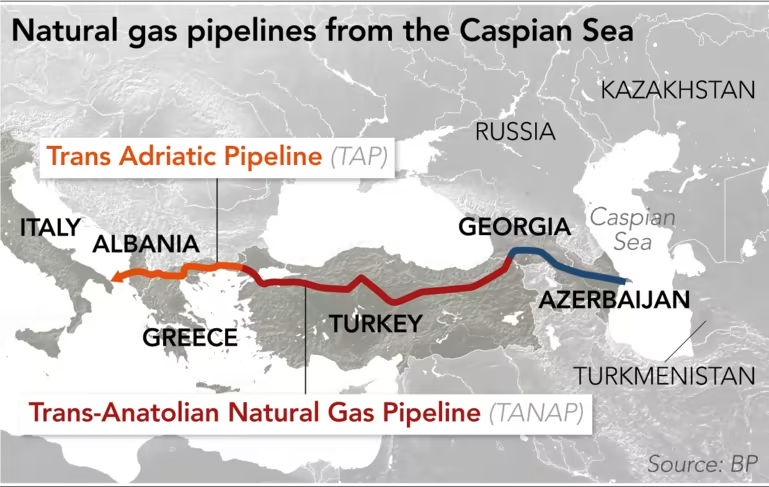

At the center of this landmark initiative is the Trans-Caspian Pipeline (TCP), a proposed 300-kilometer undersea natural gas pipeline that would connect the eastern coast of the Caspian Sea in Turkmenistan to the western coast in Azerbaijan. From there, Turkmen gas could be transported via the existing Southern Gas Corridor (SGC) through Georgia, Turkey, and into Europe.

The TCP project has been discussed for decades but was stalled due to legal disputes over the status of the Caspian Sea and opposition from Russia and Iran. However, the 2018 Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea signed by the five littoral states—Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Turkmenistan—removed a major legal hurdle and revived hopes for the project.

3. The Southern Gas Corridor: Europe’s Energy Gateway

The Southern Gas Corridor, which comprises several pipeline components including the South Caucasus Pipeline, the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP), and the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP), is already operational and carries Azerbaijani gas from the Shah Deniz field to Southern Europe. Integrating the TCP into this network would significantly enhance the corridor’s capacity and strategic relevance.

Once Turkmenistan connects to the SGC, it could initially contribute up to 10-30 billion cubic meters (bcm) of gas annually, providing a crucial lifeline for Europe amid dwindling supplies from Russia. The potential for future scalability makes this an even more attractive investment.

4. Geopolitical Dynamics: A Shift in Regional Influence

The success of this landmark project is bound to shift the geopolitical balance in Eurasia. For decades, Russia held a quasi-monopoly on energy transit from Central Asia, using its infrastructure to control prices and influence both supplier and consumer countries. With the TCP and the broader Central Asia-Europe energy corridor, this monopoly could be broken.

Moreover, China’s growing energy influence in Central Asia—through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Central Asia-China gas pipelines—has added another layer of competition. A westward route to Europe would give Central Asian countries more bargaining power and diversify their energy diplomacy, reducing dependence on both Russia and China.

The EU has welcomed the prospect, with top EU officials emphasizing that Central Asian gas will play a key role in the continent’s long-term energy diversification strategy. Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan have also responded favorably, viewing the project as a way to boost national revenues and modernize their energy sectors.

5. Environmental Considerations and Green Transition

Critics argue that expanding fossil fuel infrastructure may contradict global efforts to combat climate change. However, proponents of the TCP emphasize that natural gas, while not a renewable resource, is cleaner than coal and oil and can serve as a “transition fuel” while Europe gradually phases in more renewable energy.

Furthermore, new infrastructure can be built with future adaptability in mind—enabling hydrogen transportation or carbon capture technologies in the long term. The EU’s commitment to green energy is reflected in its funding policies, but it recognizes the need for a pragmatic energy mix during the transition period.

6. Economic Benefits: Jobs, Investment, and Energy Prices

The economic implications of this landmark project are profound. It is estimated that building the TCP and upgrading the connecting infrastructure could involve investments of over $10 billion, creating thousands of jobs across Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Europe.

For Central Asian countries, increased export revenues could finance much-needed domestic development, infrastructure, and social services. For Europe, the arrival of Turkmen gas could help stabilize or even reduce energy prices by increasing competition and supply.

Additionally, the pipeline construction and maintenance contracts are likely to attract foreign investment, particularly from energy companies, financial institutions, and multilateral development banks. The World Bank, EBRD, and ADB have expressed interest in supporting feasibility studies and environmental assessments.

7. Technical Challenges and Infrastructure Readiness

Building a pipeline under the Caspian Sea is a technically complex and sensitive endeavor. The Caspian is a unique ecosystem, and any construction risks must be managed with utmost care. Environmental impact assessments (EIAs) and multilateral cooperation will be crucial to minimize ecological damage.

On the infrastructure front, while Azerbaijan’s connection to the SGC is well-established, Turkmenistan will need to upgrade its domestic pipeline network and possibly expand the capacity of its processing facilities. Europe, too, may need to invest in additional interconnectors to distribute the incoming gas efficiently across the continent.

Security remains a concern. Pipelines, especially underwater and cross-border ones, are vulnerable to sabotage, cyberattacks, and geopolitical tensions. As such, robust monitoring systems, joint security agreements, and international coordination will be essential.

8. Diplomacy in Action: Building Bridges Through Energy

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of this project is its diplomatic dimension. The TCP and the broader Central Asia-Europe gas corridor have necessitated unprecedented cooperation among countries with historically complex relationships. Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan, for example, resolved long-standing disputes over Caspian Sea demarcation to make the project possible.

Regional organizations such as the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) and the Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO) have played facilitative roles. The EU has sent high-level delegations to Ashgabat, Baku, and Tbilisi, signaling political support and offering technical assistance.

Turkey, strategically located at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, has emerged as a key transit and diplomatic actor. By hosting segments of the pipeline and supporting regional talks, Ankara aims to reinforce its status as a regional energy hub.

9. Timeline and Future Prospects

While full implementation may take several years, key milestones are already underway. Feasibility studies and environmental reviews are expected to be completed within the next 12 to 18 months. If all proceeds smoothly, construction on the TCP could begin by 2027, with first gas deliveries to Europe projected as early as 2030.

In the longer term, this project could pave the way for even more ambitious energy integrations—such as a “Trans-Caspian Energy Grid” or regional hydrogen corridors. Discussions are also ongoing about including gas from Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan in future expansions, further enhancing regional cooperation.

10. Conclusion: A New Chapter in Energy and Geopolitics

The landmark project to deliver gas from Central Asia to Europe is more than an energy initiative—it is a strategic recalibration, a technological challenge, and a diplomatic breakthrough. It embodies the complex interplay of energy security, climate transition, regional development, and global power dynamics.

As Europe recalibrates its energy map in response to war and instability, the Caspian corridor offers a lifeline—not just for securing gas but for building new partnerships and forging a more resilient, diversified, and cooperative energy future. For Central Asia, it represents a long-overdue opportunity to assert itself on the global energy stage and reduce dependence on powerful neighbors.

Ultimately, this project may come to symbolize the future of energy: one that is cleaner, more interconnected, and less vulnerable to political manipulation. Whether it succeeds will depend not just on pipes and pumps, but on trust, transparency, and a shared vision of mutual benefit.