In the aftermath of the global pandemic, low-income nations around the world are facing a mounting crisis that threatens to derail fragile recoveries: soaring prices. From food and fuel to essential medicines and construction materials, the sharp rise in costs is placing immense pressure on households, businesses, and governments alike. For nations already struggling with debt, unemployment, and limited fiscal capacity, inflation has become a powerful and persistent adversary.

This surge in prices—fueled by a combination of global supply chain disruptions, geopolitical tensions, climate shocks, and monetary tightening in wealthier countries—has created a complex and volatile economic environment for the world’s poorest economies. These price hikes are not only pushing more people into poverty but are also undermining development goals, worsening inequality, and stalling momentum for recovery after years of economic stagnation.

The Roots of the Inflation Crisis

Several global and domestic factors are contributing to the inflationary spiral currently affecting low-income nations:

1. Post-Pandemic Supply Chain Disruptions

The COVID-19 pandemic caused significant disruptions to global supply chains. As factories closed and trade routes were interrupted, the availability of goods dropped, pushing prices up. Even as global trade resumes, logistical bottlenecks and uneven recovery rates between countries continue to affect imports and exports, especially for resource-poor nations that depend on external supplies.

2. Russia-Ukraine War and Energy Prices

The Russian invasion of Ukraine sent shockwaves through global energy and commodity markets. With Russia being a major exporter of oil, gas, and fertilizer, the conflict caused a spike in energy prices, which in turn raised transportation and agricultural costs worldwide. Low-income nations, with limited access to alternative energy sources, are particularly vulnerable to these fluctuations.

3. Monetary Tightening by Advanced Economies

To fight inflation within their own borders, the U.S. Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, and others have raised interest rates. While this curbs inflation in developed countries, it also strengthens their currencies—most notably the U.S. dollar—making imports more expensive for poorer countries and increasing the cost of servicing dollar-denominated debt.

4. Climate Shocks and Agricultural Disruption

Extreme weather events—droughts in East Africa, floods in South Asia, and hurricanes in the Caribbean—have further destabilized food production and distribution. For low-income countries, where food makes up a large portion of household spending, these disruptions are deeply felt, driving food insecurity and malnutrition.

The Human Toll of Rising Prices

Inflation, while often viewed as a macroeconomic problem, has deeply personal and human consequences in low-income settings.

Household Budgets Under Siege

In countries like Ethiopia, Haiti, or Nepal, rising prices have eroded purchasing power, forcing families to cut back on essentials like food, fuel, and healthcare. In some cases, parents are pulling children out of school to save money or putting them to work to supplement income.

A World Bank report recently estimated that over 70 million people worldwide have fallen into extreme poverty since 2021, with rising living costs being a key driver.

Food Insecurity on the Rise

Staple foods such as wheat, rice, and cooking oil have seen price hikes of 30–50% in some regions. As a result, hunger is becoming more widespread. Humanitarian organizations like the World Food Programme (WFP) have warned that over 350 million people globally are at risk of acute food insecurity, with many residing in low-income nations.

Health Systems at Risk

Inflation affects the health sector as well. Medicines, medical equipment, and even basic supplies like gloves and syringes have become more expensive. Health ministries in many low-income nations, already stretched thin by the pandemic, are now being forced to ration resources or delay treatment programs.

Impact on National Economies

Currency Depreciation

As global investors move their money toward higher-interest economies, the currencies of low-income countries are weakening. This currency depreciation makes imported goods more expensive, feeding a vicious cycle of inflation. For example, the Ghanaian cedi, the Sri Lankan rupee, and the Zambian kwacha have experienced severe declines, further squeezing domestic consumption and confidence.

Public Debt and Fiscal Stress

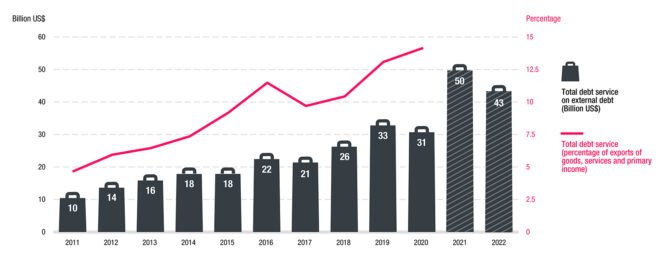

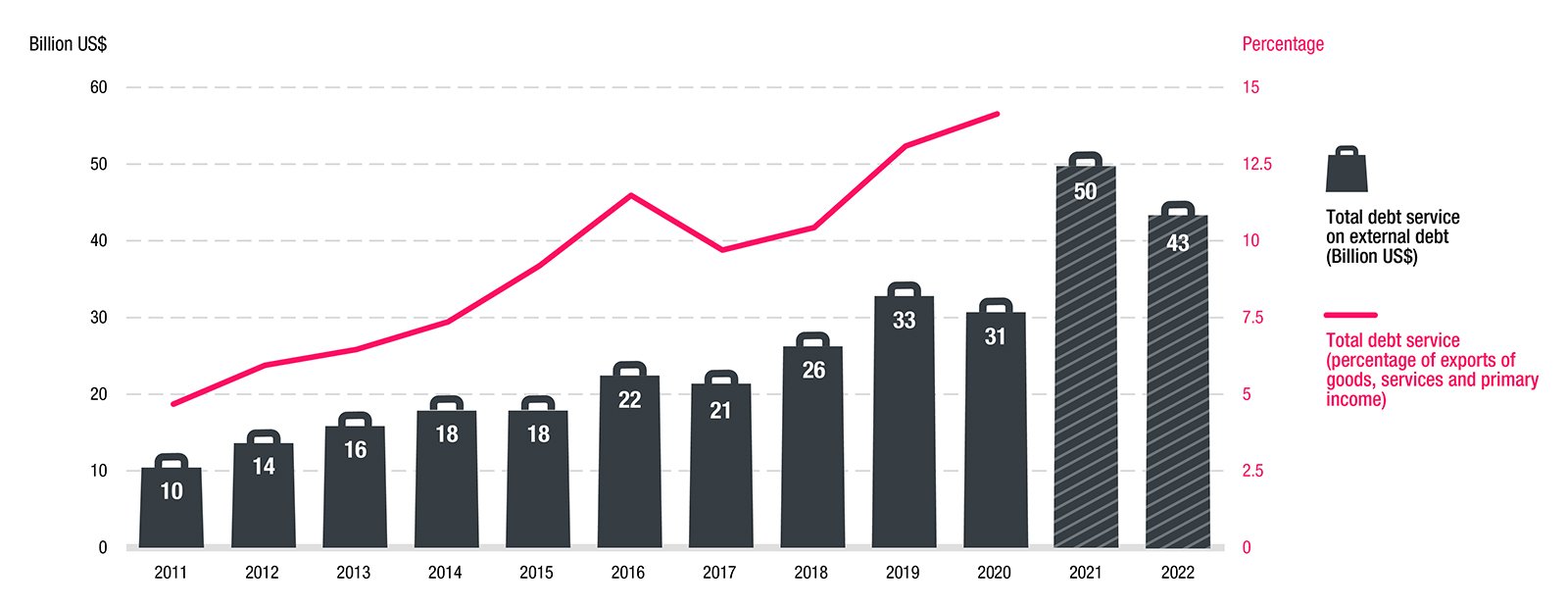

Many low-income countries borrowed heavily during the pandemic to sustain public services and support vulnerable populations. Now, with rising interest rates and stronger foreign currencies, debt repayment costs are ballooning. According to the IMF, more than half of the world’s low-income countries are either in debt distress or at high risk of it.

The cost of servicing debt means less money for social programs, infrastructure, and education—further hindering long-term growth.

Investment and Industrial Slowdown

Private investment is also being impacted. Rising input costs, along with political and economic uncertainty, are discouraging entrepreneurship and slowing industrial activity. This is particularly harmful in countries trying to boost domestic manufacturing or diversify away from commodity dependence.

Policy Responses and Their Limitations

Subsidies and Price Controls

Many governments have introduced temporary subsidies on fuel, food, or electricity to ease the burden on consumers. However, such measures are often expensive and can distort markets. In some countries, price controls have led to shortages and black markets.

Interest Rate Adjustments

Central banks in several low-income countries have responded by raising interest rates to contain inflation. However, this also makes borrowing more expensive for businesses and consumers, potentially stalling recovery and investment.

Exchange Rate Management

Some countries have tried to stabilize their currencies through foreign exchange interventions. But with limited reserves, such efforts are rarely sustainable over the long term.

International Support: Is It Enough?

The international community has mobilized some assistance, but many experts argue that support has been slow, fragmented, and insufficient.

IMF and World Bank Programs

The IMF has provided emergency financing and debt service relief to several countries, and the World Bank has ramped up funding for food security and poverty reduction programs. However, critics argue that loan-based assistance risks increasing long-term debt burdens unless paired with grants and debt restructuring.

Debt Relief Initiatives

The G20’s Common Framework for Debt Treatments aims to provide restructuring options for countries in distress. Yet progress has been slow, with complex negotiations and creditor disagreements causing delays.

Calls for Structural Reform

Development economists have called for a new global financial architecture that better supports low-income nations during crises. Proposals include special drawing rights (SDRs) reallocation, climate-linked financing, and automatic fiscal buffers for future shocks.

Grassroots Adaptation and Resilience

Despite the challenges, communities and local governments are not standing still. Across the Global South, people are developing creative coping mechanisms:

-

Urban farming and food cooperatives are helping reduce dependence on imports.

-

Mobile money platforms are enabling more efficient aid delivery and digital transactions, minimizing inflationary cash handling.

-

Community savings groups are cushioning vulnerable families from price shocks.

-

Renewable energy projects are reducing reliance on imported fossil fuels.

These grassroots innovations illustrate the resilience and adaptability of low-income populations, but also underscore the need for supportive policy and investment to scale them up.

The Role of Climate Change

An often-overlooked driver of price instability is climate change. Erratic weather patterns have severely impacted agriculture in regions such as the Horn of Africa, Southeast Asia, and Central America. With crop failures and water scarcity becoming more frequent, food inflation is likely to remain a long-term threat.

Moreover, climate-related disasters demand emergency spending by governments, further straining public finances. Climate adaptation funding—currently insufficient—needs to be dramatically scaled up if low-income nations are to build economic resilience.

A Call for a More Equitable Global Response

The crisis of soaring prices in low-income nations is not just an economic issue—it is a humanitarian emergency and a moral test for the international community. While no single policy will solve all problems, coordinated global action can help mitigate the impact.

Key areas for action include:

-

Scaling up humanitarian assistance, especially food aid and medical supplies.

-

Accelerating debt restructuring to create fiscal space for urgent social spending.

-

Investing in local food systems and climate adaptation.

-

Providing grants, not just loans, to low-income countries facing compounded crises.

-

Reforming global trade and financial institutions to be more responsive to the realities of vulnerable economies.

Conclusion: Rebuilding Recovery on Just Foundations

Soaring prices are undermining the hard-won gains that many low-income countries achieved over the past two decades. Economic recovery—already uneven and fragile after the pandemic—is now at risk of unraveling entirely for the world’s poorest.

The path forward will require bold leadership, both domestically and internationally. Inflation must be tackled not only through fiscal or monetary policy but through inclusive, sustainable development strategies that place people—especially the most vulnerable—at the center.

If low-income nations are to escape the inflation trap and reignite recovery, the global community must treat this crisis with the urgency, compassion, and strategic vision it deserves.